Remembering placenta, or maybe the sulfur mustard

his father and other troopers hacked through

in the yellow clouds of the Argonne Forest,

my father chose the Navy.

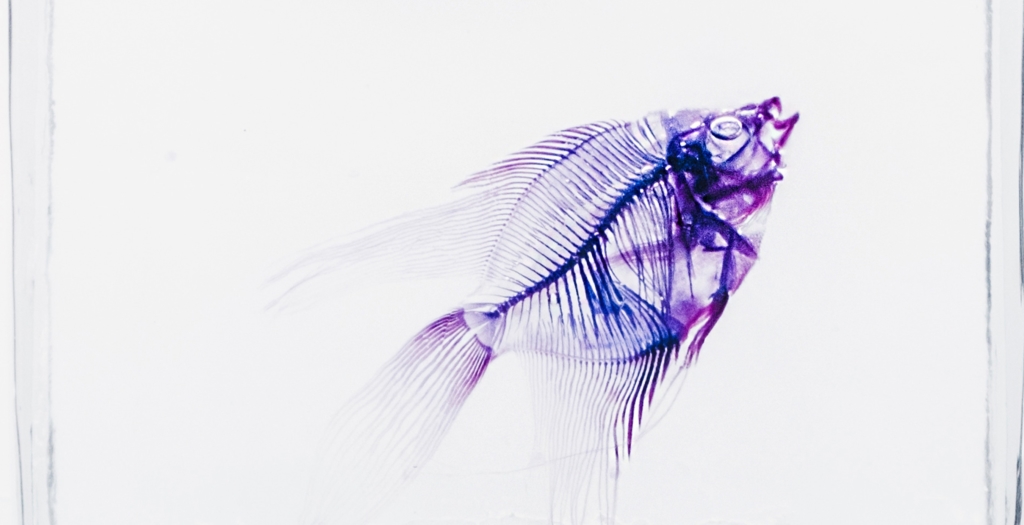

Remembering carp floating on the tense water

of Grand Lake St. Mary’s after he’d fired his shotgun

at a shadowy school, remembering his mother,

who wringed blood as vacant eyes bulged

in her twisting hands, who later served congealed

chunks as a Depression-induced side dish

to the fish flesh, my father chose to be a corpsman,

to carry medicine instead of a weapon.

Unfortunately for him, and for us, the days that lived

in infamy included so many like the one two days

after Thanksgiving 1944, when a kamikaze pierced

the flight deck, killing my father’s last best friends,

causing his heart to start collapsing over

subsequent decades like a mine with no hollow

to hide and wait, no Big John hero to hoist timbers

while others scrambled to the light.

My dad, in that buckled pit of a heart with a Japanese pilot

who survived the firefight, nursed his prisoner

back to life, as he lay in a body cast in the sick bay.

My dad discovered, sharing only the language of gesture,

his inmate’s penchant for long cheap cigars,

which he puffed furiously with his medic’s hand to help,

joyful to have escaped the Emperor’s glory.

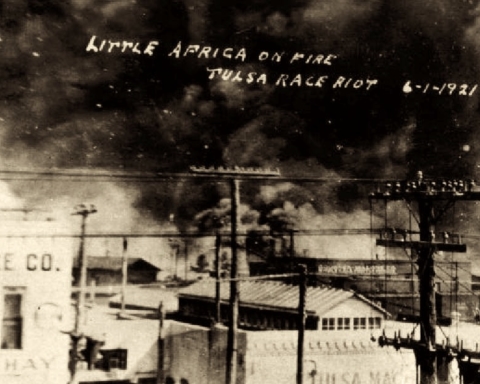

With all due respect to Cristobal Colon

and his genocidal wake, with all due respect

to Thomas Jefferson who factually slept with “property”

he smugly called “happiness” while writing about “freedom,”

with all due respect to Washington Irving,

the writer to first fill a hollow with American voices,

my story of America begins with my dad,

on an aircraft carrier heeling northward

to Okinawa, where enemies shared cigars.

———

Richard Cummins has published poems and articles in North American Review, Cottonwood, Birmingham Poetry Review and others. He is the co-author of a book on college writing. He has worked as a faculty member in community colleges and is a former college president and university chancellor living in Seattle.

———