I.

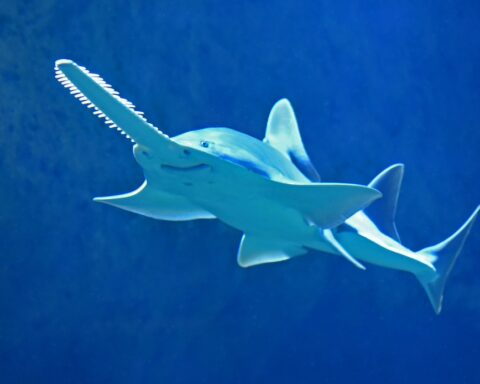

In this picture,

he is still surrounded by males

but of the two-legged persuasion

dark-skinned, uniformed for the bush,

thin-skinned with guns at the ready

Rhinos are killed for medicine

that’s never worked for thousands

of years, but they keep on trying

anyway, with the old ways,

now that some of them can afford

even the finer points of bribery

to prove its worth and

they won’t ever leave him

until he drops

or when he is finally betrayed

for both or one

of his regrown horns

by one or both guards

With his horn sawed off,

is he tamer?

Or is he just

being?

He cannot disappear in

the folds of his own skin

Called white and Northern,

we will never know

what they call themselves,

or who he was

in the time before he was captured

His groans, snorts and whines

and his pawing still escape

literal interpretation, but at times

we understand in that wordless, blundering way

humans have with animals

and then, we don’t.

Our name for him, though,

is forever a sound

that he acknowledges

no matter the tone

he will respond.

In this last picture,

his large eyes are looking out and

I think, even out beyond these men,

past the photographer,

his very nostrils sorrowing

it seems, at all that space

and no one else shares

that certain musk

He long lost his mother

thus, losing the herd

that would have raised him,

found him all the choice grazing

and watering holes and wallows,

and eventually, learning scent and savoring ardor,

naturally courting females

By now he’s tired, and he may not even know

how anymore with a female

so he’s getting help from

what they call the Petri dish;

he has had daughters in the past,

not sons, but they may be able

to alter even that in the lab

these modern animal lovers,

and like a middle-aged gourmand

he prefers alfalfa, and not the wild grasses

drier now, and of weird flavor

from which he was first nourished.

He is a living, walking trophy, the only one left,

of a troop of cousins, uncles and brothers

who long ago became fodder

their bones whitening in the sun

their flesh unrecoverable

even as meat for villagers

Their skin long turned

into whips and scourges for uprisings

and rebellions, their heads decorating

even walls here in America

proofs at once

of flaunting and suppression

II.

I’ve seen Hatari,

more than just an old moving relic

with John Wayne acting his white hunter thing,

directed by Howard Hawks,

a real white hunter, doing

his next to last movie not about women

but trapping African animals for

circuses and zoos. And I remember

the moment the rhino, cut not far from the herd

bashed the Jeep or was it the Range Rover

with the trappers on the hood

and behind the wheel trying to slip

the noose around or over

its neck, the rhino zig-zagging—

one of its short legs could be stuffed

and made into a table—galloping ahead

and then beside the snare

Then, the sun shone so bright on

the action-packed thrills and chills,

learning how to be white men with old John Wayne,

that fossil, and as ever the wrong model,

even with independence looming

and empire dying, they came

now they still come to prey and capture

as if the herds were still plentiful

and still belonged to them at any price.

The sons and daughters of the rich,

derisive of any rule, careless of boundaries,

so long as it is thinly paid for

their smiles like knives bright and flashing,

dead into the cameras’ eyes

their exploits shared onto Facebook

and Twitter back home

where everyone else in the world sees them

outraged, the hunters’ small feet Lilliput

on their big heads or necks, celebrating

their canned hunt, the quarry

who could not outrun

being corralled

before high-powered guns

with infrared sights—

the night always betraying them

And we here who fund

the sanctuaries,

the animal rights committees,

we the descendants, the guilty,

the latest inheritors of empire

have long lost our craze for buffalo

heads, tongues and hides, but not until millions

that were worshiped like gods

stretched out onto several states

were brought down and left to rot

in the prairie sun, and when there were few left

using their very bones for fertilizer

in the depleted soil.

We put them in zoos

and parks for our amusement,

had them standing on concrete,

throwing insults or even poison at them

if they resembled someone we loathed,

if they didn’t do what we expected,

as if shooting them was not enough,

and then we resurrected them,

made sure that they calved and ate

even better than the Natives that represented

the other side of our coins, shown

as they once looked—strong, unconquered

–after the land, stripped of its thin loam,

and the vegetation that survived there,

refused to give up its new fruits, when

we could not move on to the next frontier,

harvesting dust.

We brought them back slowly, painfully,

like the eagles and the condors,

shamed into counting our losses,

choosing to save them, even if they were ugly,

because gone would really mean gone

because if we called ourselves conquerors of the land,

no matter the flower, the insect, or the hoof

or the skin color, that land

does not know deeds, banks, or barbed wire,

it is never empty or subdued

or plowed over

it tries to atone, to balance

what is now out of balance,

if we do not it remembers

it recalls the disappeared

from the smallest flower

to the largest bird,

what is missing

when the sun beats down

at 150 degrees and we thirst and burn,

and when the clouds hold back their grief,

and we hunger and scatter like seeds

that will never open.

The land remembers

the ghosts that walked with Sudan and the buffalo

where once their heavy step was

unexacting, and the land returns

only shadows

In an end we can only imagine

and yet always seem to seek

the land will have its way over us

when there is nothing

and no one left

to hold us up

2015-2017

Gabrielle Daniels is a writer whose work has appeared in magazines like Sable and The Kenyon Review. She was a recipient of a Ludwig Vogelstein Foundation Grant in 2004 and the 2005-2006 Carl Djerassi Fiction Fellow at the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing, University of Wisconsin. She has been resident at Yaddo, VCCA, and the Headlands Center for the Arts. Her work will be featured in “Writers Who Love Too Much: New Narrative Writing 1977-1997,” edited by Dodie Bellamy and Kevin Killian.